Richard Weihe – Sea Of Ink

Posted 8th October 2012

Category: Reviews Genres: 2000s, Art, Biography, Historical, Philosophy, Spiritual, Translation

2 Comments

Describing the self without words.

Publisher: Peirene Press

Pages: 100

Type: Fiction

Age: Adult

ISBN: 978-0-9562840-8-2

First Published: 2003

Date Reviewed: 1st October 2012

Rating: 4/5

Original language: German

Original title: Meer der Tusche (Sea of Ink)

Translated by: Jamie Bulloch

Bada Shanren was born in luxury but chose to abandon said luxury for the robes of a monk. Inspired by his father and taught by the abbot he begins to paint, learning about himself and the world in a unique way as he does so.

A mixture of fact and fiction, Weihe’s chaptered novella spans almost an entire life in a very short time. Whilst the background is given to the reader as a non-fiction account, and non-fiction it is – the story of the Manchu conquest of China – the rest is a mostly imaginary tale of Shanren’s life. For what Weihe includes in his narrative is the sort of content you do not find in biographies: detailed thoughts and a tale that is as artistic in its written style as it is in its subject.

And there is a large amount of detail in this book; indeed just like art, it is varied, some details existing as part of the narrative, others being more about structure of subtext. A great deal consists of a subtle philosophy – sentences, ideas – often not discussed and simply just put out there, so to speak. And on the other hand there is, for example, a difference in the written style of the military non-fictional section compared to the fiction – the non-fiction reading rather like a set of bullet points without the bullet points themselves, and the fiction flowing more like the water that plays such a big part in Shanren’s life. If the non-fiction feels stilted, the fiction is liquid prose and beautiful.

The philosophy concerns art, first and foremost, but is inevitably linked to life in general. Often poetic, it draws from a pool that seems a blend of regular worldly philosophy and classical Chinese sayings, the result being highly interesting.

For me as a painter the value of the mountain is not in its size, but in the possibility of mastering it with the paintbrush. When you look at a mountain you are seeing a piece of nature. But when you paint a mountain it becomes a mountain. You do not paint its size, you imply it.

What is particularly intriguing about Shanren, at least in the way Weihe presents him, is the link between the self and the way the painter continually changes his name. Weihe himself, in the afterword, speaks of the artwork being a representation of the painter. Whilst it may not always be the case, there often seems a match of one style or atmosphere to the paintings and the name Shanren goes by at the time. He changes his name to suit the place he is at in his journey to master technique, his art, and the answers to his abbot’s questions.

As an additional point the reader may find the parallel between Shanren’s life and the life of Siddhartha Gautama, The Buddha, rather poignant. Like The Buddha, Shanren has an epiphany of sorts and decides to leave his wife and son in order to live simply with a spiritual aim. And like The Buddha – although Shanren does in fact seek a new wife after he realises his diversion from the path set by his ancestors – he comes to a spiritual awakening. The two figures shared a basic understanding of the world through Shanren’s following of the way of life created by The Buddha.

To read Sea Of Ink is to have a history lesson, art lesson, and language lesson at once. Jamie Bulloch’s translation seems at one with the original text, a good substitute where the original cannot be read. Weihe has included a lot of information and yet when reading it does not feel at all so. And the additions of the paintings themselves is a boon that allows Weihe to describe the method of painting in a way that means the reader can literally follow the brush. This written technique may at times feel overused, but it is an intriguing concept nonetheless.

If you are guided by human feelings you will easily lose your way, a wise saying went, but if you are guided by nature you will rarely go wrong.

Sea Of Ink, about art in its many forms, transcends the usual notions of appeal; it is far from restricted to those who have an interest in its most obvious aspects.

Sea Of Ink was originally written in Swiss German, and was translated into English by Jamie Bulloch.

I received this book for review from Peirene Press.

Related Books

None yet

Joanna Denny – Anne Boleyn

Posted 7th September 2012

Category: Reviews Genres: 2000s, Biography, History

2 Comments

It’s all well and good to be positive about your subject, but you can’t let it allow you to be hateful to all opposition, especially when the opposition is long dead.

Publisher: Piatkus

Pages: 327

Type: Non-Fiction

Age: Adult

ISBN: 978-0-74995-051-4

First Published: 2004

Date Reviewed: 5th September 2012

Rating: 3/5

Denny presents us with a biography of Anne Boleyn, the first wife to be executed by Henry VIII. Claiming to reveal the truth and to be unique, Denny recounts Anne’s life from young lady-in-waiting to Queen facing death.

The author begins well. Although she may be wrong about her book’s uniqueness – other historians such as Eric Ives had already produced detailed biographies – her overall purpose includes the sadly true snippet that Anne was vilified in her lifetime. She also says, “tradition has presented us with a totally unconvincing one-dimensional picture”, suggesting that she will work through this ‘picture’. And she does.

Denny provides good background context. Throughout the book she makes much use of the accounts of the Spanish ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, but cautions the reader, saying that Chapuy’s English was poor and he could only rely on spies. Likewise Denny debunks popular ideas to good effect, for example she points out that if Anne was truly as unattractive as Nicholas Sander described, she, Anne, would never have captured and held Henry’s attention for over a decade. Sanders was the person who gave us the idea of Anne being a witch with six fingers – with all Henry’s superstitions and worries, Denny’s points stand to reason, especially when you consider that Henry refused to sleep with Anne of Cleves because she looked like a horse. Yes, the description there was Henry’s own.

Something that is vastly in Denny’s favour is the way she backs up her statements. Even when she is using questionable opinions she adds a reference for where she found the information or a reference that aids her in making her point. This system enables her to bypass an issue found in many non-fiction works – unlike other writers, when Denny writes something that sounds overly romantic or fictitious, such as saying “Anne thought…” or “it was an exhausting journey” there is always a reference, in these cases state papers or the accounts of Anne’s friends. Work like this is utterly refreshing and it’s nice not to have to read such assertions with a sceptical mind.

The points that Denny makes are quite often simply fascinating, and whilst her unnecessary hatred of some of the leading players is cause for complaint (to be discussed later) this scorn of hers yields some particularly interesting facts, such as Catherine of Aragon’s silence over the issue of her virginity, silence that she kept up until Henry planned to divorce her. Intriguing too is the surprise of the Pope’s that, given Henry’s conviction that his marriage to Catherine was unlawful, he [Henry] hadn’t just gone and married Anne already. Henry was certainly an anomaly in his family when it came to scruples, as his sisters didn’t have many – Denny remarks that Margaret sought and won a divorce on similar grounds to her brother and that Mary had married the bigamist Charles Brandon without batting an eyelid.

In regards to Catherine of Aragon’s sudden revelation, to the court, of her virginity, it is interesting that this was a second concept she’d hidden from Henry, as Denny remarks on an earlier event when Catherine had pretended she was pregnant. Denny’s point is that Henry must have remembered this “pregnancy” when Catherine showed the decree of virginity, but what is truly captivating is the fact that Catherine pretended to be pregnant at all. Pretence you can understand of a woman who is aware she is considered responsible for producing heirs, but pretence would lead to sex being suspended, sex that could have made her truly pregnant.

Here it would be appropriate to discuss the overall way in which Denny portrays Catherine. Unfortunately no allowances can be made because there aren’t any – Denny hates Catherine with a passion and it is clear that her [Denny] love for Anne means she sees Catherine as a she-devil. The author does later provide a couple of quotations in evidence but isn’t it ironic that one of those references is not included in the bibliography? Plowden, who is not described and could be either a primary or secondary source for all this book is concerned, called Catherine arrogant, stubborn, and bloody-minded. This description is not enough, it is like a get out of jail free card that Denny snitched from another player, and it does not stand to reason.

The second quote is a better-known source and intriguing. Given that Catherine was Spanish and aligned her interests with Spain, it is rather telling for Denny’s conviction that the source is the Spanish ambassador, Campeggio. The man said:

“I have always judged her [Catherine] to be a prudent lady, [but] her obstinacy in not accepting this sound council does not please me.”

Compelling; but the problem with Denny’s use of this source is that Campeggio speaks of a single event, Catherine’s refusal to become a nun – which would have ended the Great Matter (Henry wanting a divorce) – and her insisting that her case went to Rome. It would have ultimately been in Spain’s interests for Catherine to become a nun as the Pope was having a difficult time with Henry; Campeggio’s words could easily be the result of in-the-moment frustration. Though this is all as much speculation as Denny’s own, the difference is that Denny gives decorum and other possibilities the cold shoulder, making herself quite the wretched writer.

Like mother, like daughter: Denny hates the youthful Mary, Catherine’s heir, as much as Catherine herself. Because of her love for Anne, Denny on occasion puts on rose-tinted glasses when viewing Henry’s actions, to the effect that she overlooks some terrible behaviour by the King towards his daughter. A prime example of this is Denny’s statement that refers to Mary’s refusal to acknowledge herself as a literal bastard, illegitimate on the grounds of Henry’s discomfort in his first marriage.

“Henry had been irritated… by her unnatural hatred.”

Here Denny calls “unnatural hatred” the anger of a daughter for a father who has treated her and her mother with distain, casting her mother aside, denying their marriage, and forcing the daughter to live away from her mother. Henry’s actions caused Mary a lot of stress. There was nothing unnatural about Mary’s hatred at all, indeed her refusal to comply with Henry’s requests was the very natural response of a girl whose father repeatedly demonstrates that he despises her.

There are two possible birth dates cited for Anne, with a few years between them. Historians have given varying reasons as to which is the more likely, but Denny’s reason is a little off. She says that since Henry preferred women to girls the older birth date must stand. But Henry did like girls – he courted and married the 15-year-old Catherine Howard when he was in his 50s.

Accounts by Chapuys, one of the Spanish ambassadors, are included throughout the book. Denny says we must take his words with a pinch of salt because he didn’t speak English and had to rely on spies, that he never met Anne. This is commonly accepted – Chapuys can’t be trusted. But when it comes to opposing evidence, Denny takes Chapuys’s word over Jane Dormer’s as to Anne’s true birth date. She takes Chapuys’s words, “that thin old woman”, as good evidence, yet Chapuys was surely being derogatory, his words are hardly nice and he despised Anne. Dormer didn’t like Anne either, but at least her words are neutral.

And in relation to Anne’s birth date, Denny says that Anne wouldn’t have bemoaned lost youth and chances of marriage if she was only in her mid-twenties. Yet mid-twenties was considered old, especially when it came to marriage.

Denny takes a very romantic view of parent-child relationships. Of the letter by Anne to her father that talks of love and obedience, Denny says that this demonstrates closeness. But in those days it was usual for such things to be written, so while it’s possible, the letter is not compelling evidence.

So Denny is struck with a hatred of Spain as well as a sort of semi-romantic notion not unlike the literal romantic notion of Fraser when dealing with Marie Antoinette and Count Fersen. Whilst it is not a case of Denny being wrong, per se, her presentation of her thoughts being undeniably correct is an example of a possible lack of interest in opposing evidence due to her convictions of Anne’s goodness. Denny has all the qualities of a historian and a fine debater but lets her bad qualities take over.

Anne Boleyn is a good book to read if you want interesting additional information. It also offers some alternative interpretations, but the reader will have to wade through malicious slander to find it, and there is a lot more of it than could be covered in a review. There is plenty of content in the book that could be used as research for other work but due to the nature of it one should be sceptical of using Denny’s opinions in any academic debates.

Related Books

David Starkey – Henry: Virtuous Prince

Posted 4th February 2012

Category: Reviews Genres: 2000s, Biography, History

2 Comments

Aiming at the goal rather than the sidelines is the best way to go.

Publisher: Harper Perennial (Harper Collins)

Pages: 370

Type: Non-Fiction

Age: Adult

ISBN: 978-0-007-24772-1

First Published: 2008

Date Reviewed: 29th December 2011

Rating: 3/5

Starkey presents to his readers the youthful Henry VIII – a man totally at odds with the tyrant he would become – in the first part of a process to show us the two very different people who came to be one king.

Starkey is a very learned man, and he quite obviously knows Henry VIII like the back of his hand. He has a talent for humour and his research is of great worth. The problem is that he has written a book the contents of which are more suited to a speculative essay. The way he has come up with elements that are ideas is no good for a book that is supposed to be factual. It is fascinating, granted, but the work is by and large pure speculation. Starkey does not base many of his ideas on evidence – which is a must when writing history – and when he does reference the work of someone else the details of the source are not thorough.

There are far too many probablys, maybes, likelys – so instead of a good account of Henry’s youth we have a lot of guesswork. And anybody can write a book on their ideas, especially if, like Starkey, they don’t feel the need to provide some sort of evidence.

Similarly, like with Philippa Gregory’s The Other Boleyn Girl, there will be many people not already well read about Henry VIII (or, in Gregory’s case, Anne Boleyn) and they will likely consider Starkey’s work true without question. While Starkey may not be vicious towards his subject, unlike Gregory, it just does not bode well. And there is the rather awkward subtle inclusion of the fact that he supports the idea of Richard III killing the princes in the tower and presents these opinions as facts.

But the more pressing thing about this book is that it does not follow in the path set out in the introduction. In the introduction Starkey says that the book is solely about Henry and that any references to other people will only be employed if they serve the purpose of explaining further the character of the second Tudor monarch. Yet the vast majority of the book chronicles the lives and ancestry of Henry VII and Henry VIII’s friends, in a way that does not link back enough to the development of the man himself. Small passages provide ideas, but they are strictly ideas as has already been discussed, and it would seem that Starkey forgot, very soon into the proceedings, that his book was supposed to be about Henry VIII. Indeed this book would be more appropriately titled Henry VIII And His Court. To use a word made infamous by Starkey, he probably got put off by Alison Weir having already written such a title.

Starkey needs to remember that he cannot simply write whatever he wants. He has a duty to both his subjects and readers, and while in regards to the former his speculations may have been accepted with mirth, for the latter that duty has been forsaken for indulgence.

And considering that readers cannot provide indulgences, and neither could Henry’s Papacy-hating Anglican church, Starkey should think again before pursuing his next inquiry with the same tactic.

Related Books

Duane W Roller – Cleopatra

Posted 26th January 2012

Category: Reviews Genres: 2010s, Biography, Domestic, History, Political

1 Comment

The propaganda presenting her as a seductress spread during her downfall, so are we in the 21st century victim of ancient history’s machinations?

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Pages: 156

Type: Non-Fiction

Age: Adult

ISBN: 978-0-1953-65535

First Published: 2010

Date Reviewed: 21st January 2012

Rating: 4/5

Roller gives us a biography of Cleopatra formed solely of information gathered from primary sources, in an attempt to give a true picture of the queen.

This is a very academic text, the sort that is useful for quoting in essays. As Roller presents only the information available to us from primary sources there isn’t all that much to record (indeed the page count is a reflection of this – don’t assume it’s a case of little effort), but the upshot is that you know the vast majority of the book is factual. What speculation there is is based on different interpretations by historians, and problematic passages in the ancient sources. Roller discusses why and how sources are likely to be biased or unbiased.

She was said to take an almost sensuous pleasure in learning and scholarship, an intriguing variant on her best-known alleged attribute.

Roller’s goal is, in fact, twofold. One is to present the story of Cleopatra as shown through the ancient sources available. The second is to debunk the “myth” of Cleopatra as a seductress, by showing what she was really like. The first he does brilliantly, in fact an element of the book that might otherwise be considered an issue – the lack of information for some parts of the queen’s life – is accounted for simply by Roller’s admission that there is no information to be had. It is very sobering and rather refreshing to read a book dedicated to providing the facts. Indeed the only speculation Roller provides is speculation based on biased sources, which is interesting, and sometimes quite fun, to read.

However the second goal is, ironically, not as well met. Roller’s goal is to dispel the myth of the seductress, but through the content he examines, both those written by her admirers and those biased against her, one can’t help but see a queen who was, yes, very intelligent and a good politician, but who also knew how to use the charms available to her as a female to get what she wanted.

And, in the case of the legendary carpet episode, Roller says quite firmly that Cleopatra did not enter Caesar’s presence in a bed sack, yet later on speaks of it as a great possibility, including precedents of its having happened before.

From page 7:

She did not approach Caesar wrapped in a carpet.

From page 61:

There is a certain credibility… because a name is provided… On the other hand, it is almost a demeaning way for the queen of Egypt to appear before the consul of the Roman Republic… Yet the bedsack device may have been common at the time…

While Roller’s determination to portray the truth is admirable, saying one thing without leniency and then saying something later that makes it possible, however great or small a possibility, isn’t very good.

There is a lot of information that isn’t about Cleopatra so much as her court, but considering the scant source material available to Roller, this is excusable, and it aids Roller in showing us who she was when the source material is silent.

Anyone interested in reading this book, which would form a very good basis for further study, should note that the appendices after the last chapter are well worth the read. One wonders why they were not included in the main text, especially as the last chapter ends without a proper conclusion.

There are flaws in this biography, and you are likely to feel slightly under whelmed by the lack of knowledge, but as factual history books go, Cleopatra isn’t bad at all.

Related Books

None yet.

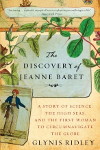

Glynis Ridley – The Discovery Of Jeanne Baret

Posted 10th January 2012

Category: Reviews Genres: 2010s, Adventure, Biography, History, Science, Social

1 Comment

Women in the 1700s weren’t supposed to join expeditions, but rules are made to be broken.

Publisher: Broadway (Random House)

Pages: 249

Type: Non-Fiction

Age: Adult

ISBN: 9780307463531

First Published: 2010

Date Reviewed: 5th January 2012

Rating: 4/5

In eighteenth century France, a poor herbalist was able to change her life by, firstly, becoming the lover of Commerson, a prominent botanist, and secondly by following him onto a ship that would take them around the world in order to gain knowledge of the new lands being discovered. To join the ship, Jeanne had to pose as a man and this led to both happiness at being able to see what few before had seen, and utter wretchedness as she strove to keep her identity concealed. Ridley presents Jeanne’s story, or at least as much as is known, introducing readers to the woman that science forgot.

Here we have perhaps the only book that details Jeanne, and while it cannot always be reliable – for reasons that will be discussed in due course and doesn’t necessarily equate to a bad thing – the information it provides is of great value and interest. Indeed you need not have a passion for social history or even science in order to enjoy it as most of it revolves around the voyage and there is a lot about the finding of new lands, meaning that there is something here for many. And it means that although Ridley rarely sways from her main subject, when she does it is fascinating in its own right.

There is plenty to devour on maritime activity, and all the hilarity that the mixture of hardened scurvy-ridden sailors sharing space with curly-wigged nobility brings. A good basic knowledge of plant collecting is here too as well as information about the initial meetings between Europe and the Americas. Ridley grants the reader insight into both sides of the story, including primary source material from the French and the thoughts of the native populations in, for example, Tahiti. And reading about the way the French, in their insecure position as travellers by sea, treated the islanders, is often a nice respite from all the information we have about the atrocious treatment that happened after colonisation.

As the theme is of a woman going round the globe at a time when women were nothing, there are a lot of mentions of gender differences as seen from Ridley’s perspective. As a woman herself, Ridley tends to give the full view, which is always interesting. Depending on the gender and opinions of the reader they may find her harsh, correct, or completely brilliant.

Copus asked his [male] guests if any man could identify the herb. None could, and all agreed the tasty addition to the salad must be some newly introduced exotic. Calling in the kitchen maid to see what she might say on the matter, Copus watched the surprise on his guests’ faces as the woman announced the “unidentifiable” herb to be parsley.

[…]

Ordinary women know what plants look like in the field and in the kitchen, while supposedly educated male scientists know only what they are told.

[…]

In an age of crude woodcut illustrations that only served to obscure identification… even the best [reference books] were inadequate as field guides.

In fact the reader is very much included by Ridley as she employs an intriguing interactivity – describing how a person might find a place today, meaning how the place has changed. By doing this she inevitably draws parallels, which give you pause for thought.

Ridley makes use of evidence and generally tells you where her information comes from, despite a lack of footnotes. However sometimes what she says, or, moreover, her point of argument, is difficult to follow because it becomes mixed in with everything else. It is understandable that when a person writes on a subject they know well, they are not going to explain everything because it may appear to them obvious, but there are a few places where more detail would have been of great benefit. There are also many many mentions of how far, or rather how not far at all, peasants would travel from their homes during their lifetime. This is an issue by itself, but it’s also an issue when the author concludes that Jeanne would have met Commerson when she was away from home and he also. Unfortunately it sounds just as romantised as the ideas of others that Ridley dismisses.

Yet this is where we come to the major point. There is a great deal of speculation in the book. And although Ridley is generally good at saying what is factual and what is not, there are times when it’s not obvious. Now there are two schools of thought here. One is that it is bad to spend a book speculating. However two is that if there is little evidence surrounding a person but an author feels the need to introduce them to the world, then speculation can be forgiven. It’s not as though Ridley is talking about, say, Louis XIV, of whom there is lots of information – she is talking about someone who is interesting for being the first woman to travel the globe but, for reasons of gender equality as well as there simply being no records, remains someone whom we can never know all that much about unless new evidence comes to light. As Ridley is not suggesting she has new evidence, indeed Ridley’s goal is transparent – that of an informer – the speculation must be viewed more favourably and seen as a positive rather than a hindrance.

The work Ridley has done could spawn a new burst of research, thus hopefully less reason for probabilities, and indeed in the afterword Ridley says that since publication a plant has been named after Baret at last.

It is up to the reader, of course, to come to their own conclusions. It’s far from an easy book to continue at times as the content often sounds archaic for the behaviours of humans back then, but the vast amount of information is worth its weight in gold (which is a lot more than can be said for the results of the expedition).

Ridley has done Baret a great service and if further research proves that some declarations are false then so be it – Ridley has propelled Baret back where she should be.

I received this book for review from Crown Publishers, Random House.