How Much Does It Help To Have A Reading Plan?

Posted 29th January 2020

Category: Chit-Chat Genres: N/A

3 Comments

I’m currently looking at a good month of reading, in fact I only say ‘currently’ because I’m hoping to improve it in these last few days of January. The goal I set at the start of the month has really helped; I suppose when it comes down to it, it’s effectively a to-do list and being more specific (yet general, ironically) has been key.

So this month I’ve had a reading road map, as it were, for what I was to read and for where I wanted to be at the end of the month. The idea of where you want to be is somewhat repetitive if you’ve a list of books anyway – you want to read those books, ergo you’ll have finished them – but having a starting book and, particularly, an ending book has worked wonders. It’s pushed me to carry on.

I’m well aware I could be heading for burnout. (If only burnout could be scheduled and managed!) Reading a lot in a set period of time tends to mean a period of burnout afterwards, and I would be all the less surprised this time since I had a fairly strict order for my reading. At the same time, I’m currently on a high. Perhaps burnout could be scheduled for March?

My road map was as I’ve previously stated – books for the podcast, early review copies, and carry overs from last year. I also read a couple of books I would’ve read in December had the festive season not pulled me into bonkers games like pretending to be a dinosaur at the intensity level of 1.

I’ve written about the concept of a reading plan before, and how whimsical reading can be great. But the more time goes on and I practise both these ‘versions’ of reading, the more I think one is not better than the other. I think I’d go so far as to say (though I could only ever have first-hand experience of my own reading) that both are best for everyone and best practice is simply definable as what is best at that given point. Sometimes you need structure in order to get it done, sometimes you really don’t, and I’d argue that the natural follow up to structure is whimsy and likewise in reverse.

Reading effectively with a plan puts paid to the worry that you might dither over the possibilities on your shelves, though this isn’t absolute; in forming your plan you probably needed to do some thinking. But, hopefully, the idea of structure aids in keeping that time to a minimum. Browsing shelves works so long as you are strict about it.

Yes, I’m also on a mission to cut back on the time I waste on the Internet.

So my answer to ‘how much does it help?’ is ‘very much – within the limits of a well-rounded reading life over all’. I’m loving my planning at the moment but I know it can’t last; but the important thing is to remember to use it when possible, and also when it makes the most sense.

Where do you fall in regards to this topic?

2020 Goals

Posted 15th January 2020

Category: Chit-Chat Genres: N/A

4 Comments

We’re in the second full week of January, I’m writing my goals, and I haven’t that many specifics. I think at this point, because I don’t want to leave it any longer, it’d be best to look at the general ideas I have and stitch them together. I achieved about half my reading goals for last year – I wanted to go back to some review copies I’d missed, which I did, and read more classics. But I didn’t get to the books I’d noted.

I know that I want and need to re-read more; this is simply a continuation of the latter months of last year. I also know that at present, I’ve a plan to finish that ever-present Thackeray and to read a good few more books, if possible, by the end of this month. I’m liking the idea of repeating that in February.

It strikes me that it might be best to concentrate on reading more in general, hesitantly moving a step further than my oft-stated ‘read as much as I comfortably can’. (Although that in itself isn’t cancelled out by trying to read more.)

I also know I want to carry on increasing my reading of classics; I didn’t manage to complete my Classics Club list – a lot did change in five years’ reading – but emphasising the idea that ‘classics’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘old’ definitely helps. In the last year I’ve noticed an increase in the number of times I’ve picked up on references to classics in other books and articles.

On the first few evenings my Christmas decorations were up, I found myself wanting to watch Outlander series 2 (I watched the first series at that time so there’s a weird feeling of Christmas to it) and following a couple of weeks’ worth of internal debate over the ‘appropriateness’ of watching it when I hadn’t read the second book, I did so. Inevitably I have now decided that yes, I should read the second book, so that’s one more specific thing to add to my list.

So, in 2020 I will aim to:

- Read more by the month, looking at shorter periods of time rather than the longer period of a year, in the hopes that that lessens any thoughts of ‘oh but it doesn’t matter that I’ve not read much in these first two, three, five months, there’s so much of the year left’. (Because I do do that.)

- Read more classics of all kinds (and if one of them happens to be the Charlotte Mary Yonge I planned for last year, great).

- Get to that Thackeray and get it done.

- Read Dragonfly In Amber

Yes, that’ll do.

Do you have any reading goals for 2020? And if you read by year, so to speak, do you ever feel complacent in the first months?

Do Adaptations Show Us Extra Meanings?

Posted 15th November 2019

Category: Chit-Chat Genres: N/A

3 Comments

Screen shot from Pride And Prejudice, copyright © 1995 BBC.

In an article about the art of adaptation, which focused on Brooklyn, writer Shastri Akella said that adaptations that are very different to their source material can make us look at other meanings that might be found in the text. This she wondered after having thought over the concept of bringing to visual life characters from literature.

I found this an interesting idea. My initial thought was to wonder how seeing other meanings in a book thanks to a visual production would work – is it possible? I was too caught up in the idea that films can never be as good as the book. Away from that, I think Akella is on to something, however today I’m going to look at adaptations as a whole rather than adaptations that are necessarily different – I’m not against differences, but I do gravitate towards adaptations that stay close to the books.

An adaptation is a single person’s (or multiple people depending on where the idea to adapt originates and goes) idea about a book. The film or television series (radio series as well?) is thus a detailed explanation and interpretation of someone’s reaction, their own visualisations of characters, location, and meanings that make up the book. It is as valid, in an objective, general, sense, as anyone else’s reactions and interpretations (supposing the director or whoever it is has read the book, of course), it’s just that putting it on screen for all to see is going to suggest, if unintentionally, that it’s a fairly definitive interpretation and a correct one, a valid one, an informed one. It is valid – in essence it’s an interpretation as good or clever, and so on, as any other, the difference is simply in the ability to put it on screen.

So, due to this, it gives the viewer (who I’m considering has read the book) an easily accessible way to discover another’s thoughts on the story, albeit that screen time is not always enough to provide the full picture. So is an adaptation that seems or is, objectively, very different to the source material useful? Unless there are reasons for the difference that move away from interpretation – say those times when directors modify aspects of the story for their own reasons (the recent Sanditon was sexed up) then the adaptation is going to fulfill Akella’s idea of this purpose of providing other meanings.

In her forthcoming book about Darcy (disclaimer – I’m reading it for review), Gabrielle Malcolm notes the 1995 BBC production of Pride And Prejudice wherein Darcy narratives the letter he sends Elizabeth about his history with Wickham against a backdrop of visual flashbacks that enable the viewer to put visuals to the letter’s content. This, Malcolm notes, was done to better infer to viewers Darcy’s better side. Austen doesn’t include the background itself – the words are all there is; whilst the choice of the production team doesn’t move in a wholly different direction to the book, it does include things that aren’t in the book (the ‘wet shirt’ scene is, of course, another) that perhaps provide slightly different insights about Darcy that you don’t get from Austen, making Darcy more accessible to the 20th century viewers, watching the series almost 200 years after the book was published.

Staying on the subject of Austen’s book – it’s in my head at the moment – the 2005 film better showed me why debate surrounds the relationship between Mr and Mrs Bennet, the changes in dialogue and chance to see characters in reality making a difference. On one side of the debate are those who believe Mr Bennet treats, and has likely always treated, Mrs Bennet poorly, enough that she was always going to become a bit over the top. On the other side are those that see Mrs Bennet as the problem – over dramatic, overbearing – and Mr Bennet the product of having it in his life so many years as to be resigned to it. I’m not sure I have an outright opinion on this – Donald Sutherland’s acting leads me to ponder the second side but that’s his influence, not Austen’s, so I’m not inclined to draw a line in the sand. I’m also not sure that Austen had thoughts either way; I think she was thinking more about what would be funny. Mrs Bennet is only a little more dramatic than the characters she is thought to be inspired by – certainly Maria Edgeworth’s Lady Delacour from Belinda, who is less ‘nervous’ but actively neglectful and deceptive struck me, upon reading about her, as a likely influence for Austen, with Mrs Bennet being inspired by Lady Delacour but ultimately being a lot nicer and unaware rather than deliberately dramatic.

There are numerous other possible influences, too, with melodrama being ‘in’ around that time. Austen was responding to her culture, to the overblown stereotypes of those who wrote a little before her time. But add a couple of hundred years to her publications and understandably a changed society questions her characters. There are far fewer limitations on what we can say and who is ‘allowed’ to have an opinion.

I do think adaptations – the ‘right’ adaptations? – can help us understand the source material better. They can definitely make us appreciate it more and they create debate, discussion. They keep our love for the work alive. It can take some getting used to when it comes to changes made or, more often, it takes some time getting used to another reader’s imagination if it differs enough from yours, but they can be useful.

What are your thoughts on the values of adaptation?

What Is The Impact Of The Amount Of Time Between Your First And Second Read On The Latter Read?

Posted 8th November 2019

Category: Chit-Chat Genres: N/A

Comments Off on What Is The Impact Of The Amount Of Time Between Your First And Second Read On The Latter Read?

Having continued to re-read, discovering more about the texts, I found myself wanting to look into this whole process further. The books I’ve been reading are on a shortish line – there are those I first read in the earlier years of my blogging (every book so far has been a ‘first read whilst blogging’ book), and those from only a year or two ago. On paper, it’s not much – the longest gap is 7 years – but when you read a lot that’s a fair amount of time. And in the context of being a reader, it’s more than enough time for changes to occur, specifically to your reader self.

I’ve pondered over whether the gap between first read and re-read has any particular merit in regards to amount of time, and in saying ‘gap’ I mean both the factual gap of time and the gap in relation to how many books have been read in the meantime; the more books you get through, the more you’re likely to forget ones further back, an understandable drawback of avid reading. (That, I think, is something that can be lived with.)

When it comes to the question of whether being able to remember less or more of the book makes for a better re-reading experience, I don’t think there’s a right answer. Not being able to remember – and this can, as noted, happen no matter how long ago (or not so) you first read the book – means simply that you’re going to enjoy your re-read in a different way. It might take a bit more time for you to ‘get back’ to where you might have been had you remembered, but that’s not a bad thing. Whilst being able to remember a lot means your further appreciation of the book – all those things you didn’t notice the first time – might happen sooner, not remembering the content doesn’t mean it won’t happen. And of course remembering the book – most likely the story, themes, and any impression the characters made on you – may well cause you to need a bit more time to get into the book again due to the chance you wonder why you’re re-reading it right then. (By this I mean you wonder in general – ‘why am I reading this again when I’ve already read it?’)

My present experience of this pertains to Samantha Sotto’s Before Ever After, which I started a couple of days ago. I remembered I loved it; I had the benefit of having reviewed it (though my review, in 2012, seems to me now incredibly amateur and lacking in literary context); and I remembered the basic plot and my liking of Sotto’s hero. But I didn’t remember that the author started her book in the present, and I didn’t remember the character of Paulo, the young man who arrives at 26-year-old Shelley’s front door to tell her that her husband, who died a couple of years previously in his early 30s, is his grandfather and managing a restaurant on the other side of the world. (Yes, it’s as good as it sounds.)

And – to my shame, right now – I have had this book on my favourites list ever since I read it.

My re-read of Montgomery’s The Blue Castle gave me a completely different feeling for the book, enough that I wondered if I shouldn’t write a new review. (I opted for a Reading Life post.) In brief, my first read had me me laughing, my re-read had me looking at the poignancy and dysfunction. I laughed very little.

This moves us to the way we can change as readers. We change as a whole – our reading preferences change, we read differently, we’ve got a lot more reading behind us to inform new reads – but I’m thinking specifically on a per-book basis: we often change in the context of being a reader of that book, whichever book is currently in question. My second read of The Barrowfields showed me the progress I’d made by the way of reading more classics and in general knowledge of other classics. My time in-between first and second read – a year and several months, not long really – allowed me during the second read to understand and often be simply able to note more literary references than I had that first time, and, in so doing, I was more aware of the idea that the best way (for me) to read the book that second time was to look up anything I came across that I didn’t know, no matter whether it struck me as important or not.

This, then, is why ‘amount of time’ is and has to be a malleable concept when it comes to re-reads. It’s the amount of time in the context of you, of your self as a reader, your reading background, and so on. It’s also not always related to how much you enjoyed the book that first time, in fact I’d argue that loving a book so completely can make you forget the details sooner. It’s all too easy to think that because you loved a book so much, you’re never going to forget it. The only definite, I reckon, is that you’re unlikely to forget the experience of reading it and your feelings at that time.

I don’t know if I ‘need’ to read The Blue Castle again – I probably will but it’ll be for the same reason I re-read it earlier this year: the simple enjoyment of it. I’ve identified a likelihood of ‘needing’ to read The Barrowfields again, in a few years time, perhaps, to see how much more I might enjoy it, to see how much newly accessible content there is for me to take away. This of course circles back to the idea of there possibly being a limited amount to take.

There is obviously no real way – one might use the buzzword ‘organic’ – to measure the effect of the passage of time between reads. You’d have to erase the book from your memory, and selectively at that, keeping some of it back, but it is something I’d like to keep in mind as I continue what has become a real pleasure – re-reading what I’ve loved.

I’ve always worried about the fact that a re-read necessarily means one less new read in your time, but when done right – and again, that’s subjective – it’s incredibly valuable.

What are your thoughts as to time on this subject?

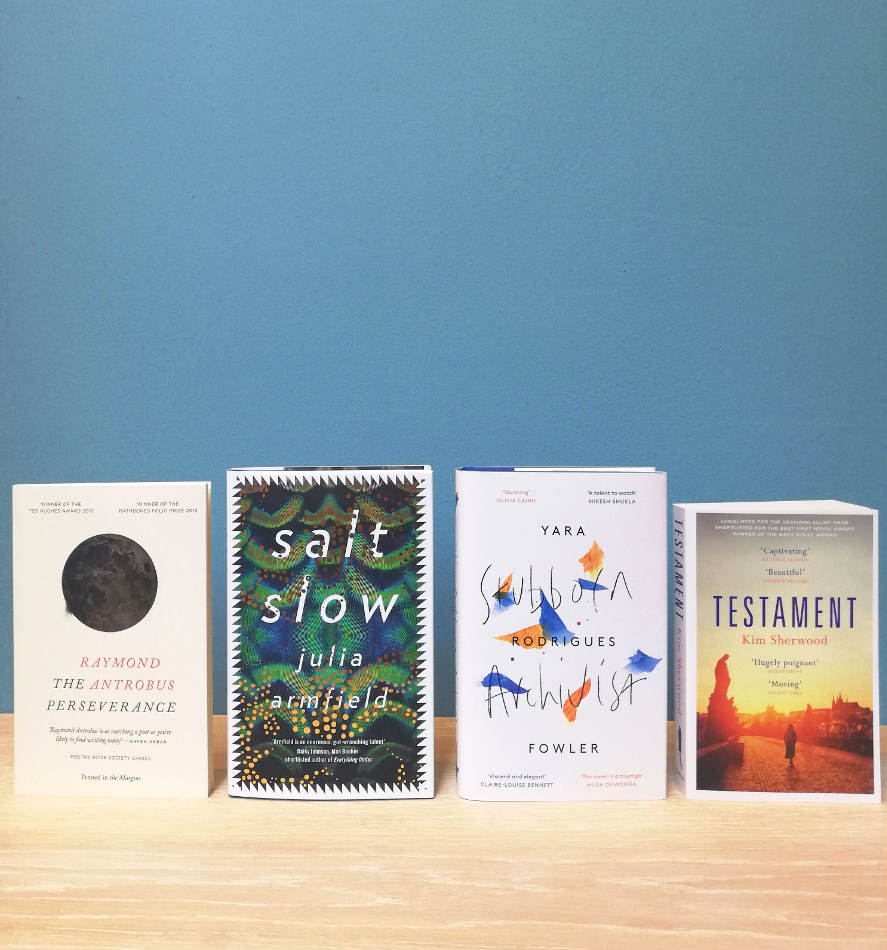

The 2019 Young Writer Of The Year Shortlist

Posted 4th November 2019

Category: Chit-Chat Genres: N/A

1 Comment

To me, now, it wouldn’t feel like November without this. The shortlist was announced yesterday following a record number of submissions – over 100 books were sent in this year. Awarded to a writer under the age of 35, the prize was won last year by Adam Weymouth for Kings Of The Yukon, a non-fiction narrative. He was joined on the shortlist by Imogen Hermes Gowar, Fiona Mozley, and Laura Freeman. The award was won in 2017 by Sally Rooney, 2016 by Max Porter, and 2015 by Sara Howe.

This year’s authors are Raymond Antrobus for the poetry collection The Perseverance, which won the Rathbones Folio Prize earlier this year; Julia Armfield for short story collection Salt Slow (one of her stories won The White Review Short Story Prize last year); Yara Rodrigues Fowler for the novel Stubborn Archivist, a Desmond Elliott Prize longlister; and Kim Sherwood for the novel Testament which has won the Bath Novel Award. This year’s winner will be announced on 5th December.

Due to the number of submissions this year, there are five judges – alongside The Sunday Times’ Andrew Holgate are Kate Clanchy, Victoria Hislop, Gonzalo C Garcia, and Nick Rennison.

This year’s shadow panel of bloggers are Anne Cater, David Harris, Linda Hill, Clare Reynolds, and Phoebe Williams. Each year’s shadow panel have so far awarded a different author than the one who won officially so it’ll be interesting to see if this year’s group do the same. Perhaps I’m biased – okay, I am – but I do look forward most to the bloggers’ choices.

I’m particularly happy to see Antrobus on the shortlist; whilst I’m yet to read his collection in full I’ve read examples from it and read a fair amount about the poet’s work and background, which I mentioned in the post linked above about his Rathbones Folio win.

Have you read any of the books? What’s your opinion on the shortlist?